With the rise of streaming content online from the likes of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu Plus more and more American's are cutting the cord on cable. Cable television subscriptions have peaked and are now falling. Things would likely be much worse if it weren't for cable television's saving grace: live sports. If you want to catch the week's biggest sports match-ups, you're going need a cable subscription. For most games, it's impossible to legally watch online.

The only way to get ESPN and other top sports channels is to purchase a bundle of channels. At Time Warner Cable, in Cincinnati, OH, the cheapest way to get ESPN is to buy the Standard TV Bundle. It includes 70 Channels and starts at an introductory rate of $50/month + tax. In other words, it's impossible to get ESPN without buying access to CNN, HGTV, TBS, Bravo, Animal Planet, E!, Nickelodeon and the other standard cable fare. Unsurprisingly, many sports fans could care less about these channels. Whenever, channel bundling is discussed online, you'll quickly come across the same complaint:

"I don't want to pay for all that crap I don't watch, I'd rather pay a fraction of the price for those few channels I actually watch."

It's a sentiment that sounds reasonable and resonates with many consumers. It has even found political support. In August of 2013, John McCain introduced the Television Consumer Freedom Act of 2013 which would require cable television providers to offer programming "à la carte".

However, the effect of bundling on consumers is a tricky issue, the economics of which is quite nuanced. This article will explain the economics of product bundling: why companies bundle products and whether this hurts consumers. In the process, you may find that product bundling may be a good way to price products in your business.

To understand why companies bundle, you need to understand a little bit about the economics of pricing. For simplicity, we'll assume that the cost of producing an additional unit (known as marginal cost) is zero. This accurately reflects the cost structure of cable companies. Once the cable lines have been laid and the television programs have been produced it doesn't cost them anything to flip the switch and turn on your cable. Similarly, many online products like ebooks, software and mp3s have a zero marginal cost. It's pretty much free to send bytes over the internet. When marginal cost is zero, maximizing profit is as simple as maximizing revenue.

Whenever you raise the price of your product two things happen:

- Some people stop buying (hurts revenue)

- You make more money off of everyone who keeps buying (helps revenue)

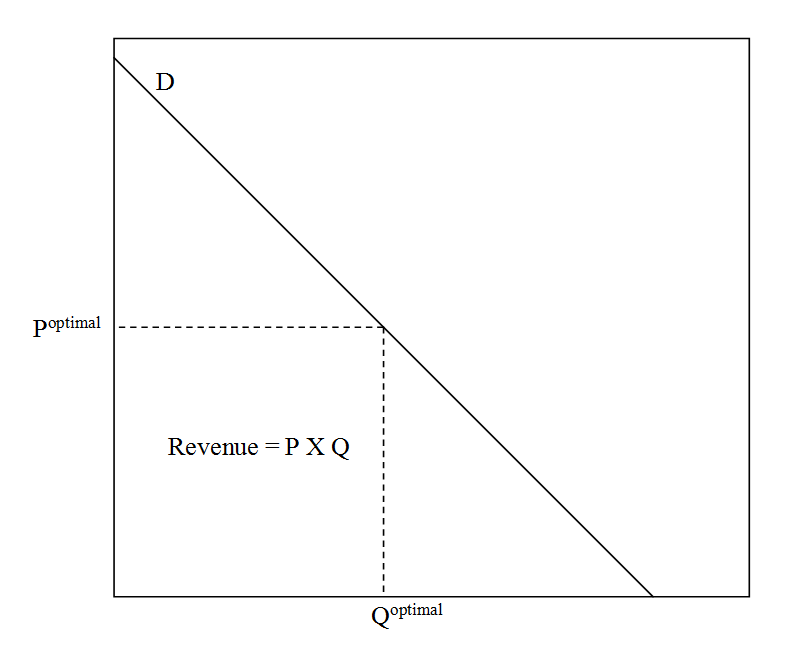

To maximize revenue, you need to find the optimal tradeoff between these two forces. Practically, you can do this by starting with a price of zero and raising prices until the benefits of #2 are perfectly offset by the costs of #1.

Visually, we can see this by using a demand curve. If you've never seen a demand curve before, check out this Khan Academy video to learn the basics

For a given demand curve, the revenue maximizing price is always exactly halfway down the demand curve.

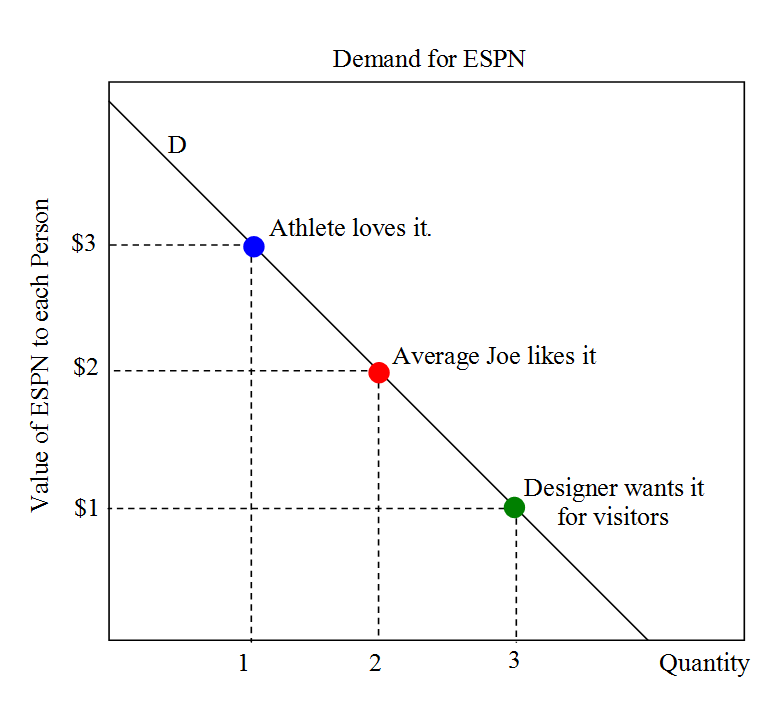

We can illustrate that this is true by using an example and a few numbers. Imagine an isolated island with a cable company, Island Cable, trying to sell ESPN as a standalone channel. The island only has 3 people: an athlete, an average Joe, and a designer. Everyone gets some value from having ESPN, but this value differs from person to person. The athlete is obsessed with sports and watches every night. The average Joe watches occasionally when his alma mater is playing. And, the designer only wants ESPN so that his friends can watch it when they come over. The numeric value each person places on having ESPN can be seen in the following graph:

What price should the cable company charge to maximize revenue?

- At a price of $3, only the athlete will buy and revenue will be $3.

- At a price of $1, everyone will buy and revenue will be $3.

- At a price of $2, the athlete and the average Joe will buy and revenue will be $4. Since this brings in the most revenue, it is the optimal price. As predicted, this is the price halfway down the demand curve.

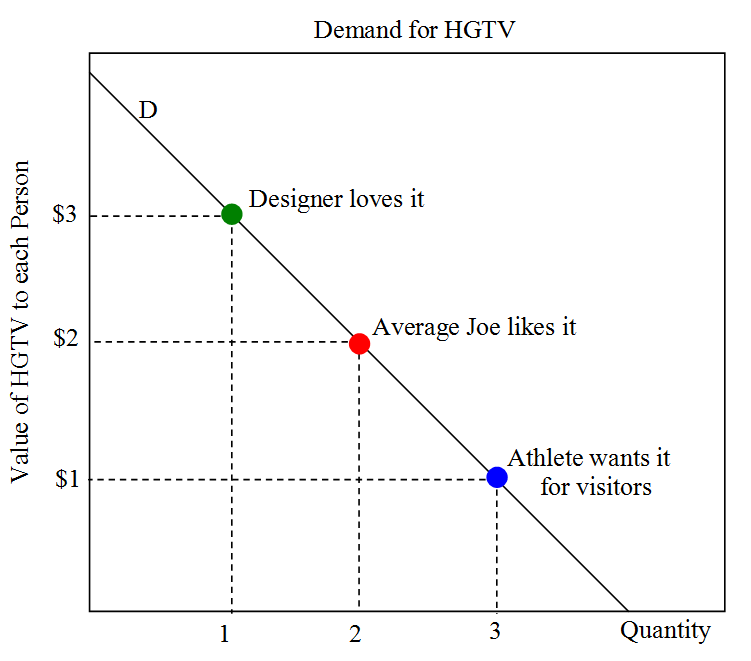

Suppose that Island Cable also offers HGTV a real-estate and home improvement channel a la carte. Suppose demand for HGTV looks like this:

This demand curve looks identical to demand for EPSN. However, a closer look reveals that the location of the people on the curve has changed. The athlete and the designer have switched places. This makes perfect sense. Preferences for ESPN and HGTV are typically negatively correlated. The more people like ESPN, the less they tend to like HGTV and vice versa.

It's easy to work out that the optimal price is also $2 and revenue will also be $4.

When Island Cable sells HGTV and ESPN individually and chooses the optimal price for each, it will make $8 total. This is a lot of profit! But, here comes the interesting part: Island Cable can make even more money if it bundles ESPN and HGTV together.

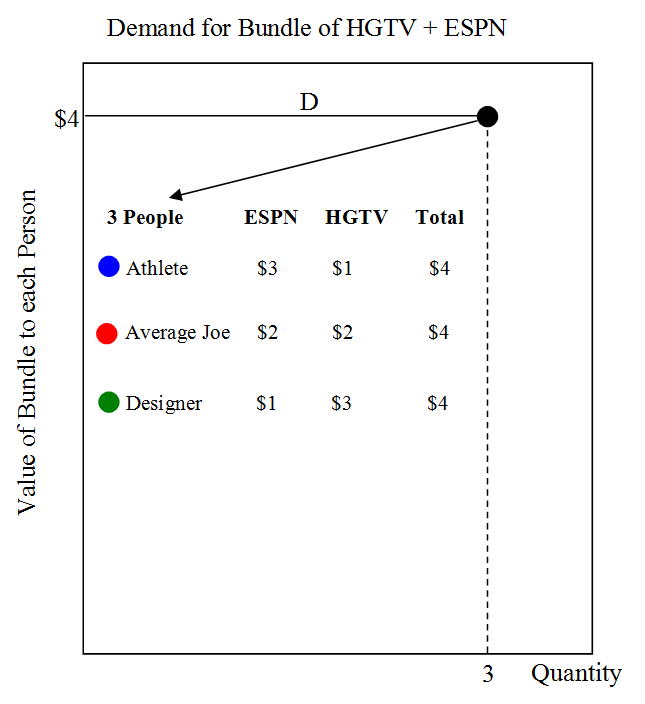

Let's see what happens graphically if Island Cable stops selling the channels individually and only sells a package containing both HGTV and ESPN. To create this demand curve, we simply add the value of ESPN to the value of HGTV for each person (colored dot). Doing so gives us a demand curve like this:

Everyone now gets $4 of value from the bundle! Island Cable can charge $4 for the bundle, everyone will buy, and revenue will increase to $12. In this example, bundling increases revenue from $8 to $12, a 50% increase!

What is going on here? Because preferences for the two channels are inversely correlated, bundling the two goods makes demand more similar (or homogenous) flattening the demand curve. In our simple example, everyone gets the same value from the bundle: exactly $4. The demand curve is now perfectly flat. When the channels were sold separately, Island Cable couldn't charge a high price to people who loved a channel without scaring away customers who only liked that channel. Now that everyone values the bundle equally, this constraint has totally disappeared.

This illustrates a powerful concept:

You can often increase your pricing power by bundling products together.

Is bundling good for consumers?

In our simplified example, consumers are worse off because Island Cable is able to set a price that extracts every last bit of surplus from the consumers. This particular result is driven by our assumption that preferences are perfectly inversely correlated. More generally, bundling will transfer some (but not all) surplus from consumers to the firm. However, it is possible for bundling to improve consumer welfare by making goods available that otherwise wouldn't be profitable. For example, suppose that in the above example HGTV and ESPN each cost $5 to produce. When sold individually, each channel only brings in $4 in revenue. Therefore, it wouldn't be profitable to produce either show!

However, by bundling the goods together total revenue would increase and exceed total cost! Channels that are unprofitable under à la carte pricing become profitable under bundling. This increase in product availability makes consumers better off. If the government stopped cable companies from bundling, a number of cable channels would almost certainly go off the air.

Should you use bundling in your business?

Bundling doesn't work for all businesses. It works best when:

-

The marginal cost of your product is low.

Bundling is all about giving people goods that they get some, but not a lot of, value from. This works out when you are sending bytes over the internet. It doesn't work so well with physical things. -

Your customers have wide and varied interests.

My gym membership is a good example of smart bundling. I can lift weights, swim, or play basketball all for one monthly price. I like some of these activities more than others, but I get value from having access to all of them. By bundling these options together, the gym is able to flatten the demand curve and increase its pricing power. I'm better off because the gym is able to offer a greater variety of activities than would be available if activities were sold individually.

In contrast, you shouldn't bundle products that have no cross-over appeal. For example, it doesn't make sense to bundle rap and country music together since people tend to like one or the other but not both.

A closing thought

A final benefit of bundling is that is simplifies things for your customers. It's easier to sign up for Spotify than pick out a new album every month. It's more relaxing to order the buffet than pour over the menu. Fewer choices makes the buying decision less stressful and minimizes buyers remorse. That translates into more sales and happier customers.